Everything is scary at night. Darkness is scary, and light too, when you do not know where it comes from. Or who is coming just behind it. Or who is coming in the dark. Shadows grow bigger and change shapes, objects come alive, skin turns into scales, and scales stretch like fingers, vegetation turns into a creature… or, worse, a human.

You hear noises, breathing, whimpers, a high-pitched mosquito, the floorboards creak and the window batters in the wind, a door being opened far away, steps in the yard, and steps on the stairs, each noise echoing, and there is a pain in your temple, another pain in the crease of the crotch; waiting under the sheets. Will he come? Will they come again?

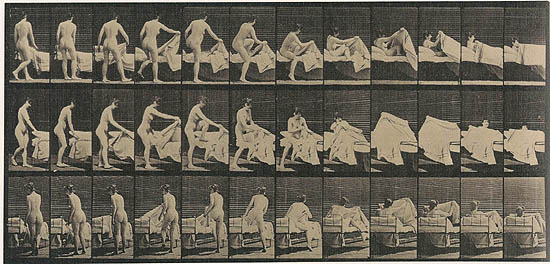

Men writhe under the sheets and cannot find sleep.

If they sleep, nightmares will awaken them, the nightmare that has been chasing them since childhood.

You spread the sheets, you get into bed, you switch the light off, you close your eyes, you wait.

You think.

You remember things.

|

| Eli Lotar, Slaughterhouse, 1929. |

|

| Eli Lotar, Slaughterhouse, 1929. |

|

| Eli Lotar, Slaughterhouse, 1929. |

|

| Francis Marshall, Mauricette at school |

|

| Chris Marker, La Jetée |

Wrapping yourself in your sheets.

Wrapping yourself in fabric.

Tying knots. Attaching cords.

Protecting yourself from lurking evil.

Curling up into your own skin, so that your body won’t melt away.

A woman lifts open the curtain hiding a doorway to a room; above, amulets are hanging. December 2012. Foua (Guinea).

A woman lifts open the curtain hiding a doorway to a room; above, amulets are hanging. December 2012. Foua (Guinea).Surviving — fighters

And by daylight, too, the struggle against fear. Tying yourself up in protective laces, wrapping amulet cords around your arms, your neck, your chest, wearing talismans on your bare skin, or written on the canvas of your clothes, tracing magical formulas, letting the ink run onto you through the sweat of sleep or struggle.

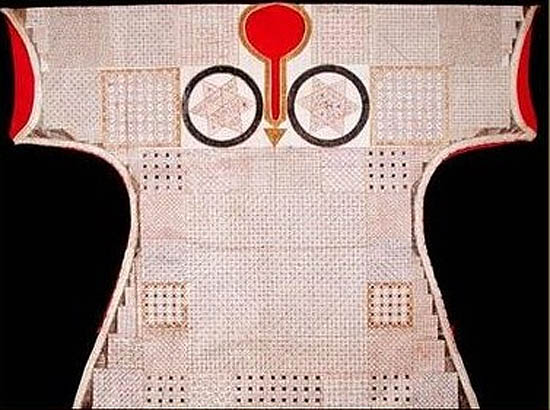

In Dakar, nowadays, when you fear misfortune, when life is tough and dreams are out of reach, when fate must be helped along, you consult those who know. Among the solutions offered is fashioning talismans of writing, whose origin can be found, not in Africa, but in the Muslim world: the most common patterns go back to al-Bûnî in the thirteenth century. They already inscribed the same talismans in medieval Persia, Morocco or Mali, they wore the same shirts in the Ottoman court.

Once they are drawn on a sheet of paper, talismans are handed to a shoemaker who sews them into various sorts of amulets. Sometimes, the talismans are drawn on a shirt and the client, who may not be able to read Arabic, can only see in the writing its magical part, without grasping the meaning of the words – writing as a pure symbol.

Those tunics from Dakar echo the marvellous Ottoman talismanic shirts displayed in Topkapi: princely shirts, Sultans’ shirts, shirts of dignitaries as anxious about their fate as today’s street wrestlers and politicians in Dakar. The use of an amulet is personal, and its lifespan variable. If it works, it is treasured, passed from generation to generation or shared between dear friends; but often, it passes away with the one who possessed it. If it fails, whether due to contact with impurities, or merely to provide the desired result; it is destroyed, buried or simply tossed aside. A costly tunic worn to win elections or a match is abandoned after a defeat. These magic objects, disposed of after use, make up Alain Epelboin’s collection, accumulated over 30 years, collected from those sifters of garbage in the dumps of Dakar.

The making of princely shirts, worn to protect from all manner of risks, illnesses, bewitchment, wounds of war, obeyed rules many times more intricate than the shirts found nowadays in African dumpsters; humble replicas. To be worn on bare skin, they were sewn from fine fabric and drawn upon using specific pigments. Sometimes, to guard themselves from illnesses, Ottoman dignitaries and their children wore tunics cut from relics of the inner drapes of the Kaaba, or of the mausoleum of the prophet Muhammad in Medina.

When a crown prince was still a child or a adolescent, shirts were already made and embroidered; he would receive them together with the throne. For their creation, many were called upon: oneiromancists, astrologists and numerologists; they were charged with a choice of verses from the Quran, prayers, summons of spirits, talismanic formulas and geometrical figures – circles, squares, pyramids, ellipses and arcs, each charged with a numerical value, and all destined to adorn the shirts of the prince. The cut itself, and the number of pieces of fabric to piece together, were of upmost importance. The ritual making of the shirt can be traced to gnostic letterist mysticism developed in Iran in the fourteenth century, the doctrine of hurûfiya.

This shirt, to be worn under armour, was meant to protect the wearer during battle or to insure victory. The main field is divided in square or rectangular panels, filled with text from the Quran, while the edges are inscribed with the 99 names of God. Large medallions on the front and the back contain various inscriptions: the shahâda and other prayers, as well as Quran verses emphasizing the protective action of God.

The shirt of Prince Cem could demonstrate the ineffectiveness of the talisman: Prince Cem never became a Sultan, but was in all likelihood poisoned far from his home.

However, the neck of the shirt, still sewn shut, seems to have never been opened, meaning the shirt was never worn, and could not, therefore, guard Prince Cem from the effects of poison.

Surviving again — women

Worlds, eras, beliefs may be different, but magical thinking remains similar: carrying certain words against your skin, wrapping yourself inside embroidered messages, this enables you to keep on living in spite of the fear they inspire. These objects simply become more intensely private, an intermediary is no longer needed, and the recipient of the talisman – a woman, more often than not – becomes its creator.

Here she is, sewing, embroidering, writing her thoughts on those pieces of linen which women had available in the nineteenth century, in the needlework box which followed them everywhere, from childhood, an integral part of a woman’s habitus.

So many of those drab works subsist nowadays – alphabets, pious sentences and monotonous wishes in packed stitches of red silk, where writing is no longer drawing, no longer scenery, where sentences are void of all meaning and retain the mere form of empty signs. Still those mock writings can suddenly catch a voice. Become a language.

Maids, working girls, mad girls, attached to the rags they keep in the pocket of their aprons, they adorn them with embroidery, the only language that is not forbidden to them.

Rag that remains rag, rag that becomes a dress, rags that become a vest. Broken messages. Embroidered clothes that let them wear their own words against their skin.

“Yes, Madam.”

When called, she answers.

“No, Madam, not yet.”

The clock ticks in the dim room. Outside, it is raining.

|

| Agnes Richter's Jacket |

When called, she answers.

When not, she does not speak, she does not sing.

In the dark desert of the kitchen, she embroiders, never lifting her eyes.

The clock ticks on in the dim room.

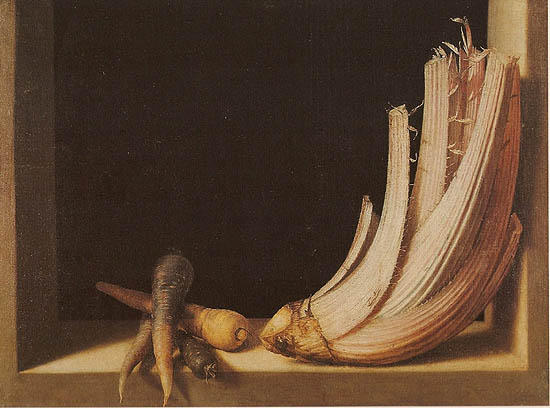

She embroiders, eyes down, holding her breath. She avoids making eye contact with the cabbage which hangs over the sink.

Juan Sanchez Cotàn (1560 – 1627), Cabbage, melon and cucumbers (c. 1602), San Diego, San Diego Museum of Arts.

Juan Sanchez Cotàn (1560 – 1627), Cabbage, melon and cucumbers (c. 1602), San Diego, San Diego Museum of Arts.

+is+written+in+Arabic+and+continued+with+an+Ottoman+Turkish+translation.+It+is+a+talisman,+made+for+a+certain+Mustafa+ibn+Ibrahim..jpg)

,+deuxie%CC%80me+moitie%CC%81+du+XXe+sie%CC%80cle.jpg)

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire