And, anyway, what if you should die? Face the otherworld and its perils? Have the duty to proclaim your rank there and have it acknowledged?

Multiplying the images, enveloping the bodies with sumptuous fantastical figures, writing magical words all around your shroud to scare away the evil one.

(Here, I must open a long parenthesis for what is obviously a mere digression: the story of a fake. For centuries, far from Turin, a precious cloth passed for the only true “Holy Shroud”, that shrouded Christ himself: the shroud kept in the Cistercian abbey of Cadouin, in French Périgord.

That Holy Shroud was first mentioned in 1214: the relic may have belonged to the bishop of Le Puy, who would have acquired it at the capture of Antioch, during the First Crusade (1098).

The thaumaturgic shroud was widely venerated during the entire Middle Age; thousands of pilgrims on the Path of Saint James went out of their way to worship at the abbey; illustrious people, kings even, from Richard the Lionheart on his way to crusade, to Saint Louis of France, came and knelt at the Shroud. To keep it safe from the looting and violence of the Hundred-Years War, the Shroud was entrusted to the church of Notre-Dame du Taur, in Toulouse. As could be expected, the people of Toulouse refused to give it back for many years; the recorded power of the shroud was extraordinary: up to 1644, more than 2,000 miracles were recorded, including 60 resurrections.

Eventually, after it was sent back to Cadouin, the miraculous shroud was still displayed each year to the pilgrims on September 8, until 1935.

That year, a Jesuit priest, intrigued by the motifs on the woven strips of the shroud, sent a copy to the School of Oriental Languages in Paris. Gaston Wiet, the director of the Arab Museum of Cairo, came to Cadouin to examine the piece. Alas, he recognized it as a tirâz from the time of the Fatimid; a cloth manufactured in the workshops of the caliph. The method of weaving was complex: in a canvas of linen, the weaver inserts a strip of silk for decorative purposes. Upon it, Wiet could decipher inscriptions in the Kufic script of Arabic: they call upon Allah, glorify Muhammad his prophet, and record for posterity the names of Caliph al-Musta’lî (1094-1101), one of the last Fatimids, powerless since the Nizarite scheme; and his all-powerful vizir, al-Afdal, who outlived three Caliphs. For more than 700 years, the faithful had worshipped an object not much more ancient than their abbey, and consecrated to another faith.

In short, the pilgrimage ended.

I had seen it some twenty years ago. Very damaged, it has now been restored, to the extent possible; but it is not on display anymore. Through a strange paradox, a facsimile is now showcased instead: an authentic fake of a fake shroud of Christ.

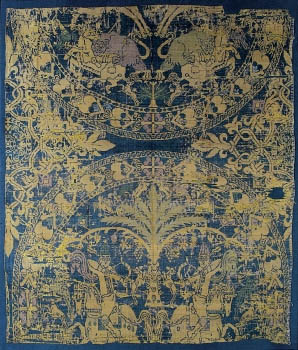

The only images I could find of it are rather underwhelming:

In my memory, the shroud was of very large size, discolored white, fully encircled with a delightful edging – but memory can play tricks.

End of digression – here I close the parenthesis.)

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, French monasteries made great use of those prestigious shrouds, employed to protect the remains of saints, now forgotten, but who had made a city famous, and rich. Most of these cloths came from the East – from Byzantium or Persia – and, contrary to the Cadouin “shroud”, they did, in fact, shroud relics, sought-after collective talismans.

Embroidered or woven calligraphies, fabulous beasts, miraculous origins – those shrouds thus became talismans, used for protection of other, even more powerful, talismans.

The most beautiful of these, in my opinion, the one made to be contemplated again and again with wonder, is the shroud of Saint Germain from Auxerre, one of the first bishops of Frankish Gaul, who died in Ravenna in 448. It is a large rectangular piece of silk, 2.36 meters long, adorned with four eagles. For many years, it was believed that it had been offered by Empress Galla Placidia to honor the remains of the saintly bishop. The cloth is, in fact, much more recent, and would have been used for translating the saint’s body into a new burial chamber in the eleventh century; the eagle is a frequent motive in Byzantine art, and the high quality of the fabric bespeaks the skill of Constantinopolian workshops around the year 1000.

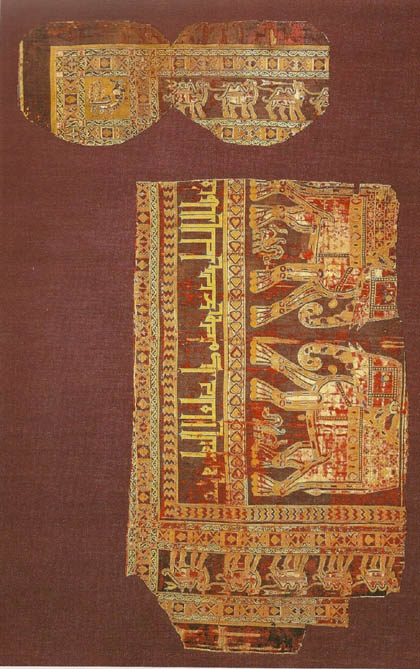

Remoter still, the Shroud of Saint-Josse, now conserved in the Louvre: the cloth comes from a shrine kept at the abbey of Saint-Josse-sur-Mer, in Northern France. Already in 1843, when the relics were translated, there remained only one fragment from the huge cloth, shrouding the saint’s skull and one, slightly larger, around the bones. That cloth is mentioned in a charter from 1134, as a gift from Stephen Blois, count of Boulogne, brother of Godfrey of Bouillon and, together with him, leader of the First Crusade. It is a fragment of “samit”, a unique example of Sassanid motives in Persian Islamic silkwork, produced in Khorasan, by Merv or Nishapur. Two ranks of elephants face each other, separated by hearts and enclosed by a line of smaller camels. A kufic inscription : “blessing and happiness be upon chief Abû Mansûr Bukhtekin, may God extend his years”. Abû Mansûr Bukhtekin was a Turkish emir, executed in 961 for rebellion – the cloth, that we can now roughly date, did not bode him well.

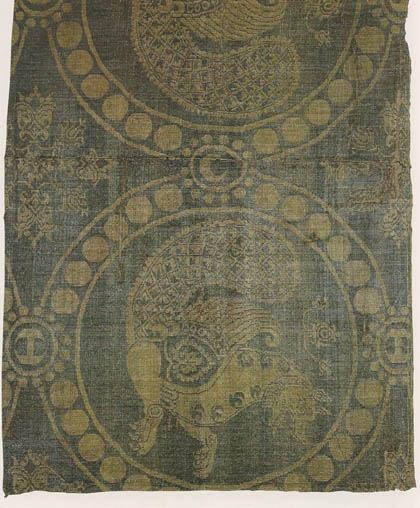

Shroud of Saint Calais : Bahrâm-Gûr's Hunt, silk produced in Constantinople, IX century, Saint-Calais, Sarthe (0,77m × 0,64 m).

Shroud of Saint Calais : Bahrâm-Gûr's Hunt, silk produced in Constantinople, IX century, Saint-Calais, Sarthe (0,77m × 0,64 m).Older yet, the gorgeous shroud of the church of Saint-Calais was most probably used for the translation of the saint’s remains in 837.

The shroud shows a hunting scene: on both sides of a palm tree, surrounded by deer, birds and dogs, two horsemen, dressed in an Iranian costume, with a Sassanid helmet, take aim with an arrow at an onager, that a lion holds by the throat. This motive goes back to an episode of Shah Bahrâm-Gûr’s life (420-438): the monarch managed to kill with a single arrow both an onager and the lion that attempted to devour it. This typical hunting scene, featuring a horseman, was also used in Byzantium to glorify the imperial might.

As for the relics of Saint Helena, they were stolen in Rome, on behalf of the Abbey of Hautvillers, in Champagne, in the year 842. The cloth, known as the “shroud” of Saint Helena, was probably woven in Byzantium not long before the theft; it displays, in a medallion, a senmury (dog-dragon with a peacock’s tail, a figure frequent in Sassanid art).

This poor Helena then travelled further, to Paris – and it seems that she is still there (without her shroud), in the crypt of the Saint Leu-Saint Gilles church. Her shroud would have guarded her through the antireligious destructions of the French Revolution – Saint Calais and Saint Josse were not so lucky.

So, if cloth is not enough, what is left for us?

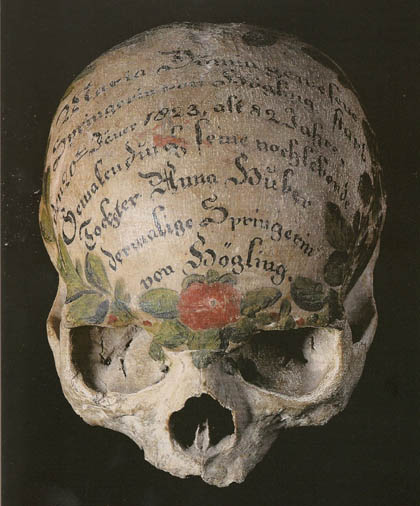

Writing again, after death, writing and drawing, covering with signs what is left of a body.

The

skull of Maria Domin, keeper of the ossuary of Högling, Bavaria, who

died at 82 years of age; painted by her own daughter who inherited the

office (nineteenth century). Since the fifteenth century, skulls were

painted in Högling – women’s with gentians, carnations and roses, men’s

with oak or laurel wreaths.

The

skull of Maria Domin, keeper of the ossuary of Högling, Bavaria, who

died at 82 years of age; painted by her own daughter who inherited the

office (nineteenth century). Since the fifteenth century, skulls were

painted in Högling – women’s with gentians, carnations and roses, men’s

with oak or laurel wreaths.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire